Bicester’s Great War

A lot of the action that took place during the First World War can be followed by looking at the stories of the many local men who fought, and died, during the conflict. These are the stories I’ve researched of just a few of those brave men and women, from Bicester and the surrounding villages, who made the ultimate sacrifice for King and Country.

Following an escalation of hostilities across Europe, Britain declared war on Germany on Tuesday 4th August 1914. The Bicester Advertiser, published a few days later, describes that week as follows:

Never within living memory have events stirred the local public so much as the happenings of the last week. With dramatic suddenness Europe has been plunged into a state of war, the ultimate result of which it is impossible to foretell. The details have been followed day by day with such eagerness and the excitement that has been created during the week is worthy of record.

The Order in Council, calling out the Army Reserves and embodying the Territorial Force, was issued on Tuesday, and the copies exhibited at the Post Office attracted large crowds, eager to read the summons. This had been expected since the events of Sunday, when the Naval Reserves were called out, and the proclamation relieved the great tension which many had felt during the preceding days.

The news of the declaration of war by England against Germany was received early on Wednesday morning. By the early motor on that day the local Territorials proceeded to Oxford, to report themselves to headquarters. By the first post on Wednesday morning the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars received their call to arms, and several of the local men started at once, catching the eight o’clock motor, whilst others followed later in the day.

Many of the colleges of Oxford were thrown open for the use of the military, and facilities given, without reservation, for the use of the kitchens and dining halls. The Examination Schools in the High Street are to be used as a base hospital, and already a staff of nurses are making arrangements to that end in connection with the Red Cross Society.

Owing to the depletion in the ranks of the police force, caused by the calling up of the reservists, it was necessary to summon special constables to duty on Wednesday (August Fair day).

The Western Front was the main theatre of war that Britain was involved in during the conflict, and the bit that everyone thinks of when talking about the Great War. It stretched through France and Belgium; with Britain, France, and their allies on one side, and Germany and Austria-Hungary on the other.

Since the reserve forces, and those already on active service, went off to France almost immediately when war was declared, it didn’t take long for the casualties to start racking up. And, just 20 days after war was declared, Bicester suffered its first loss.

The Battle of Mons, on 23rd August 1914, was the first major action of the British Expeditionary Force in the War. The Allies clashed with Germany in Belgium and, at Mons, the British Army attempted to hold the line of the Mons Canal against the advancing German Army.

Although the British fought well and inflicted disproportionate casualties on the numerically superior Germans, they were eventually forced to retreat. The retreat lasted for two weeks and ultimately took them to the outskirts of Paris before they could counter-attack, in concert with the French, at the Battle of the Marne.

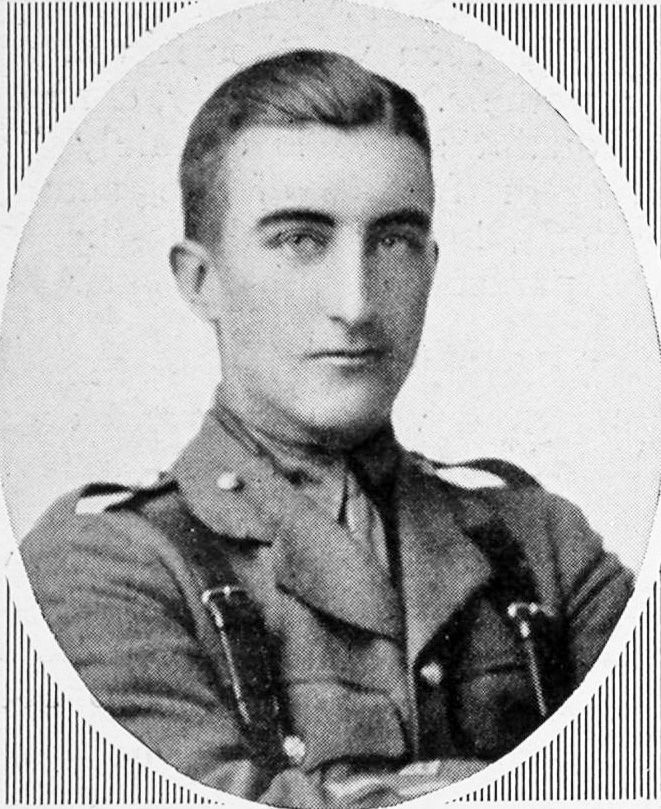

Lieutenant Charles Hoare, of the King’s Hussars, was killed on 24th August while protecting the infantry during their retreat from Mons. He was the son of Charles and the Honourable Blanche Hoare, of Bignell Park.

His parents had always intended for him to join the Royal Navy, even educating him in Dartmouth. But, in the end, he chose the Army and joined the Hussars in December 1913. His love of Polo, hunting and point-to-point racing making him ideally suited to a cavalry regiment.

A short while later, through the French and Belgian countryside, the German and Franco-British armies were busy continually trying to outflank each another. Heading further and further north in what became known as the “Race to the Sea”.

The “race” ended at the northern coast of Belgium on 19th October, when the last open area was occupied by Belgian troops who had retreated after the Siege of Antwerp. The outflanking attempts had resulted in a number of encounter battles, but neither side was able to gain a decisive victory, and instead just dug themselves in once they reached a stalemate.

After the opposing forces had reached the coast, both tried to conduct offensives, leading to the mutually costly and indecisive First Battle of Ypres on 19th October, which lasted for 34 days.

The Battle of Ypres was actually made up of a series of smaller confrontations. One of which, the Battle of Nonne Bosschen, or Nun's Copse, involved the 2nd Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry attacking, and ultimately defeating, the Prussian forces that were hiding out in the wood. This likely involved Joseph Morris, from Bletchingdon, Jesse Jones, from Horton-cum-Studley, and Edgar Golder and Maurice Hirons, both from Bicester. All of whom were serving in the 2nd Ox & Bucks and died around that time.

Private Golder's case actually demonstrates the "organised chaos" that was prevalent in that stage of the war. He is now officially recorded as having died on 31st October 1914. But, at the time, he was unofficially reported as just having been wounded in the head.

By February 1915 his family still hadn't heard anything from him, the War Office had stated that they had no information about him, and his battalion headquarters just confirmed that he had not been placed on the official missing or casualty lists. His mother continued to write to him, only to have most of her letters returned, unopened, with "hospital" written on them.

Eventually, on 3rd February 1916, 15 months after losing contact with him, his mother received a letter from his battalion headquarters telling her that, as he had been missing since October 1914, the Army Council concluded that he was dead, and had died on 31st October, or since.

Sadly, this is the case for a lot of the men who died in action. If there was no body to bury, then no one could ever be completely certain what had happened to them.

An example of the carnage, and a good show of the British "stiff upper-lip", concerns Private Basil Martin, from Bicester, who died from wounds received in action at Ypres. His Sergeant, J.H. Giblin, wrote to Basil’s mother as follows:

Our regiment was driving the enemy from a strong entrenched position. We commenced this attack on the 29th, and the good old corps advanced like one brave man – a sight which I shall never forget. Every man was eager to fulfil his duty, and to gain honour for his King and Country.

We were fighting an army ten times our numbers, but the brave British did not care for that, and we set out with a strong line, which, however, was soon mown down and reduced to a thin line. Regiment after regiment was falling, and it was almost like a slaughter-house.

I was ordered to collect what men I could and try to drive a party of Germans from a trench. I gathered 80 men, including your son, and I had gone but fifty yards before I lost 60 of them. The enemy opened a most murderous fire upon us from a flank. Their artillery shelled us just like hail stones, and much machine-gun fire, still the boys (that is, what were left) went on to complete their task, and succeeded in driving the Germans from their position.

I knew your son very well, and he was always a good and respectable soldier. He was well-liked by the officers, NCOs and men, and was well on his way to a higher rank.

I could give you more details of the War, but the hardships are too bad to describe. I hope this war will be over soon; many a poor mother’s heart is broken, and many a woman has lost her husband.

Your boy had a good death. All those who were wounded were attended by the priests, and those who were able to speak all made a good confession. Other poor sinners are continually saying their prayers in the trenches. It would make a man pray who had never prayed in his life before. Thank God all the Roman Catholics who have died, all died happy deaths.

Now, Mrs Martin, you must try and cheer up; I know it is hard. I have almost fifty letters to write to mothers and wives, and I don’t know how to break the news to some of them. They are mostly young married women. One has three babies – the youngest born while her husband was away, poor creature! He is dead, and what can I say? They are all similar cases. Cheer up!

By mid-November the weather was getting decidedly colder, and on 20th November the ground was covered in snow. Frostbite cases started to appear, and the physical strain increased. Understandable among troops who were occupying trenches half-full of freezing water, falling asleep standing up, and being constantly shot at and bombed from opposing trenches just 100 yards away.

So things quietened down and, over the winter lull, the French army established the theoretical basis of offensive trench warfare, originating many of the methods which became standard for the rest of the war. Ultimately leading the Western Front to become the industrial slaughter-house that has come to characterise the Great War.

Despite the poignant and unique ceasefire of Christmas 1914, complete with its impromptu football match, war on the western front continued to develop into 1915. Constant attempts on both sides to break the stalemate just resulted in more and more casualties.

Letters, such as one written to a Banbury gentleman at the end of January 1915, emphasise just how fed up everyone was, and how the realisation that it wouldn’t "all be over by Christmas" had demoralised troops on both sides. It was written by a member of the 2nd Wiltshire Regiment, serving on the front line, and he says:

The Germans have not got the fortitude of our troops. Two nights ago 200 of them came up to some trenches and wanted to give themselves up, but their own officers drove them back with revolvers, and for some strange reason our men did not fire. Can you imagine British troops surrendering because of the hardships they have to endure? I can't.

We hear rumours that if the war is not over in a few weeks then many German regiments are going to give themselves up - evidently the enemy are getting very demoralised. No doubt you heard that we talked to them on Christmas Day and Boxing Day, and then they said they wanted to get back home again - and so do we all - but we'll see the job through first.

I have seen ruined villages with not a house or a farm left standing; dead cattle dotting about the fields everywhere; little mounds and tiny rough crosses on them marking soldiers’ graves; and a hundred or more soldiers buried in one common grave. I have seen a woman wring her hands and burst into tears as she passes the remains of her farm - and then go back to a tiny hovel to tend six children, while her husband fights for his country.

Truly war is a horrible thing, and one must see its awful ravages to realise fully how terrible modern warfare is.

But those in command weren't quite so ready to give in and end it. They instead put their faith in the ever evolving technology of the day to help them win victory. Over the course of the war, mustard gas, flamethrowers, machine guns, and tanks, all sprung out of the determination of both sides to win at all costs.

But, as with most technological innovation, it often takes a few iterations before all the bugs are worked out. Unfortunately, with weapons development, those iterations often resulted in some quite severe accidents.

Grenades were relatively simple weapons to use, but a man would have to be able to throw it at least 100 feet, just to protect himself from the blast. So, in typical British fashion, it was deemed that cricketers, especially those with a good bowling arm, made the most effective bombers. However any the front line infantry, cricket players or not, might be required to use them, and so had to be trained.

It was on one of those grenade training exercises where Guardsman Albert Hawkins, from Chesterton, met his fate. He was serving with the Grenadier Guards, when, on 11th April 1915, while practising grenade throwing, one exploded in his hand, killing him instantly. This was just a few days before his 21st birthday.

He had been with his regiment for almost two years, and had seen service in several engagements, including Ypres. In a letter to his brother a short time before his death he said he was only fifty yards from the German trenches and had had several narrow escapes. One in particular, when a bullet passed through his breast pocket, narrowly missing his chest.

A lot of the men who served in the war wrote home regularly, and many of their letters were printed in local newspapers. One of the most prolific writer local enlisted men seems to have been Private Arthur Coppock.

On the outbreak of war, being a National Reservist, he volunteered for active service at the first parade of veterans. He was immediately sent for training, and was very quickly drafted to the front.

Early in December 1914 he wrote home to his wife saying:

I have had Harry Clifton down to see me, and we had half an hour together; having a drink and a smoke. We had a laugh and a chat over old times.

I have seen George Hines; he was riding by us, but he gave no answer when I shouted to him. I think he had gone too far to know who it was. Of course we Bicester fellows make enquiries about one another, and we like to see one another when we get a chance.

My chums are two Oxford men, and we get on well together; we enjoy our tobacco in the trenches, and share out like three little chickens. We get all sorts of fags and tobacco sent us, so we do not go short of a smoke.

Then, in a letter to Mr Arthur Herbert at Christmas 1914, he states that he was in the charge of November 11th, when they drove the Germans out of the wood at Nun’s Copse:

It was a great surprise for the enemy; they were big men but had small hearts inside them. The two days round that charge were the best of my life.

He then goes on to talk about the goat skin coats that were keeping everyone warm and explain that, at the time of writing, he was resting in his dug-out, and, as the men had been paid a few times, he was able to go out and purchase anything he required.

Then, in early January 1915, he wrote to his brother saying that:

We had a good time at Christmas, considering all things. It is raining every day, and this makes it hard work for us getting about. We have been in the firing line again since Christmas, but I have no fear that the time will come when I shall be home with you all again.

I have been in a few hot corners since coming out here, but have got through them all right so far. On one occasion we saw the German dead laying about in bunches. We were resting one day, but were called back as the Germans were attacking, and the enemy knew that we had come back to their cost. We squared them up and made them pay the penalty for doing us out of our rest.

On 1st February he wrote excitedly to his wife about some upcoming leave he had just heard about. But then, just two days later, he wrote to his brother, stating that:

The leave has been stopped and the men recalled to the firing line. But, with good luck, I think that the leave order will soon be renewed. I will be heartily glad when it comes my turn, so that I may see a bed again. I haven’t seen one since I left England, but at least all the fellows are the same.

A month later, in another letter to his brother, he wrote:

The regiment came out of the firing line on March 16th. The trenches occupied were only 100 yards from the German lines, so that there was continued rifle and shell fire throughout the night.

A shell burst 6 yards from me the second day I was in the firing line. I was laying in my "dug-out" at the time, and was the nearest man to the shell when it burst. One of the men of our section came round to see if I was hurt, but I told him the Germans had not got me that time!

The nose of the shell went straight through the back of the trench and into the next one, where some more men were. A man picked it up, but it was so hot that he dropped it pretty quickly.

Anyway, we had a good laugh over it and no one was hurt.

At the beginning of May he writes again to his brother who, by then, had joined the Oxfordshire Heavy Battery.

In his letter he teases his brother that if he ever gets to France then he will never see any Germans, unless they are taken prisoners, as the Heavy Battery is always about 4 miles behind the front line. He then adds:

If I get done in before you get out here, don't forget to have your own back; I know you will have the guns and shells to do it with. Try and reach the Kaiser with one of your long-rangers, as he is the "bloke" we want to get hold of."

Unfortunately, there is many a true word spoken in jest. And few weeks later, on 21st May 1915, it was reported in the Bicester Advertiser that Private Coppock had been seriously wounded in the head.

A postcard was received by his wife on the Sunday following the article, saying:

Dear wife,

Just a line to let you know I have had a very good day to-day. I have not much pain, but it is a slow job however.

From your loving husband, Arthur.

From the handwriting it seems that it wasn't written by him, but had been dictated to a hospital nurse instead. On the same day his wife also received the official notification of his death.

A newspaper report the following week stated that:

Private Coppock leaves six small children, one of whom was only a month old when he was “called away” to do service for his country.

Most cheerful and interesting letters have been received from him, many of which we have published. A sentence typical of the British soldier occurred in one of his letters recently to his brother, which was not published with the rest of the letter at the time. It ran – “They tell me mother and my wife worry a great deal, so I just write them some long cheerful letters and tell them everything is all right, but of course it is not very grand."

Despite the latter knowledge, which bore more significance than words could express, no word of complaint was ever written by Private Coppock, who has earned his place in the list of Bicester Heroes.

In the Summer of 1916, as an attempt to hasten an Allied victory, the largest battle of the Western Front, the Battle of the Somme, began on 1st July. It lasted almost 5 months and cost the lives of over 450,000 British troops, 200,000 French, and somewhere between 400,000 and 600,000 Germans.

Ultimately the key objectives of the allied forces were unfulfilled, but they did succeed in penetrating 6 miles into German occupied territory, the largest advance since 1914.

The first day of the battle is recorded as the worst day in the history of the British Army. On that one day alone they suffered over 57,000 casualties, including 19,240 who were killed in action.

Locally, we lost four men in the fighting that day, namely Privates Frank Clifford, Harry Kightley, George Morris, and Lieutenant Philip Norbury. But, in total, the 5 month battle cost us 74 men, 20 from Bicester alone.

One of those, Private Howard Clifton, of North Street, was killed on 23rd July, while serving in the Ox & Bucks Light Infantry. Captain Pickford, his commanding officer, wrote to Private Clifton's parents saying:

It is my sad duty to tell you that your son “Punch” was killed in action this morning.

The regiment had the very difficult task of capturing a German trench which was holding up the advance of the whole line, and did the job very successfully, but not without some rather heavy casualties, among whom was your son, who was killed when accompanying his officer, Second-Lieutenant Hutchins (who was dangerously wounded at the same time), in the attack.

We shall all miss him terribly, as he was a general favourite throughout the company and an excellent officer’s servant as well as a jolly good soldier.

Your son was slightly wounded a few days previously, but very bravely said nothing about his wound until the battalion came back to billets afterwards.

He was always cheerful, whatever the circumstances, and the mess will not be the same without his happy face. May God comfort you in your great sorrow.

A comrade of Private Clifton also wrote to his parents, telling them that:

I could not let this sad trouble which has befallen you pass without offering to you my sincere sympathy, as your dear son had been my friend ever since he came out.

He was a good soldier and a good comrade, always cheerful and bright, and ever ready to lend a helping hand to any of his comrades. I can assure you that we, in the officer’s mess, miss him very much, and I have no doubt that you have now had a letter from our captain, who, I know, considered him a good soldier, and a good servant.

You have one consolation, that he died as he had lived – a soldier and a true comrade.

Another of the local Somme losses, Private Henry Ashmore, died on 6th August from shrapnel wounds he received during the battle of Delville Wood.

He went into action as part of the 7th Border Regiment on 1st August, and all went well for him until about 5:30am on the 6th, when he was busy issuing the daily rations to the men and a shell burst very near him. He was rushed to the nearest dressing station, but died very soon after his arrival.

He had been home on leave just a few months before that, where he married his fiancé, Mary Dixon. They had a short time together as newlyweds before he returned to the front line. But that was the last she ever saw of him.

In May 1917 Sergeant Ernest Lambourne, a native of Bicester who had emigrated to Canada in 1913, was awarded the Military Medal whilst serving on the Western Front with the Canadian Machine Gun Corps. He received the award for "conspicuous gallantry during the operations on Vimy Ridge, between the 9th and 13th April 1917". He was in a section which went forward in the initial assault and established a strong point in some bomb craters, capturing "one of Fritz's guns" in the process.

The citation reads:

The section performed most splendid work and their personal courage was most marked. Sergeant Lambourne displayed exceptional courage and coolness of mind leading the section during the assault whilst under heavy fire.

Unfortunately, he was killed only a few weeks after receiving the award, in possibly the most humane death you can imagine on the Western Front. At 11pm on 4th June a bomb, dropped by a German aeroplane, exploded just outside the tent in which he was sleeping. He was killed instantly in his sleep without ever knowing what was coming.

The chaplain who officiated his funeral wrote to his parents, still living in Alchester Terrace, saying:

It was a sad blow to the officers and men of the unit to which he belonged, for he was universally beloved and respected. They desire me to express their deepest sympathy for you in your great bereavement.

You have this consolation as a precious heirloom, that your son died a hero in the most sacred cause that ever called men forth to arms. He will not be forgotten either by Heaven or earth. God will reward him for the sacrifice, and a grateful country will keep his memory green.

I buried your son in one of the authorised military cemeteries, well at the back of the firing line, in the presence of his officers and comrades. While a funeral at the front must, of necessity, lack much of the reverent adornment to which we are accustomed at home, nothing could surpass in true dignity the noble sympathy and affection displayed by the soldiers for a fallen comrade.

In the course of a few days a cross will be erected over your son’s grave, while the grave itself will be tended and cared for by soldiers set apart for that special work.

I’ve already mentioned accidents during training, but not all accidents were war related, they just happened to take place while the men involved were on active service. Two such cases happened to men from Bicester in 1918.

The first, Sapper George Hines, is the end of quite a tragic tale.

He was an old soldier, having enlisted in the 13th Hussars in 1900, when he was 20 years old. He went to India in the early part of 1902 and served almost seven years there before his time expired. He then came out of the army, but remained on reserve.

When the First World War broke out he was called up straight away and rejoined his old regiment, proceeding to France at the end of September 1914. He was in the retreat from Mons and other big engagements, and was wounded in early 1917. He came to England to recover and stayed about four months, then returned to France.

In November 1917, his reserve period expired and he transferred to the Royal Engineers. Then, a month later, he returned to England again when his wife suddenly became ill. His wife died early in January 1918, and he returned to the front line a little while after.

Then, on the night of 2nd April, he was sleeping when the building he was in caught fire. It seems that the rest of the men with him managed to get out, but sadly he never made it. Tragically, he left behind two children, a boy and a girl, aged eight and three respectively. Orphans who had lost both parents in the space of three months.

The second local victim of a tragic accident was Private Cecil Hedges. He died in hospital in St Albans on 15th July 1918.

Two months earlier he had been serving his King and Country in France and was enjoying a bathe with some other members of his regiment when, in taking a dive, he struck a comrade who was swimming beneath the water with such force that it seriously injured his spine.

His parents were notified that he was dangerously ill on 27th May, and on 5th June he was brought to a hospital in London, where he seemed to be making some recovery. But his condition began to rapidly decline on the 16th, and on the 23rd he was moved to a hospital in St Albans, where he passed away a few weeks later.

Private Hedges had joined the army in March 1917, enlisting in the Cyclists’ Corps of the Oxfordshire Hussars. But before being sent abroad he was transferred to the Worcesters, and eventually went to France in April 1918. He then joined a trench mortar battery, where he was serving at the time of his accident.

His funeral took place in Bicester, and was reported as a simple but impressive affair. Reverend C.H. Rose, the Wesleyan Minister, officiated, and there was a very large number of people present, including many connected with the Wesleyan Church, at which he had been a regular worshipper, in addition to being one of the Sunday School teachers.

Now our story returns to the Somme, where Captain Horatio Fane died on 11th August 1918, from shrapnel wounds received the day before, during the Battle of Amiens.

He had gone to France with the Oxfordshire Hussars at the outbreak of war, serving there for the next four years. He had been wounded earlier in 1918, and only left Bicester after sick leave on the 27th June.

He was very popular with both the officers and men of his regiment, and was always highly spoken of by the men who came home on leave. In civil life his frank and open manner won him many friends, and an article about him in the Bicester Advertiser declared that "the town of Bicester is the poorer by so promising a career being cut short". He took an active interest in many things connected with the town, and was a member of the Urban District Council up to the time of his death.

A month later, on 18th September, Horatio's younger brother, Major Octavius Fane also died on the Somme from wounds received in action. He was the youngest son of Captain and Mrs Fane, of Bicester House, and the third son they had lost to the war.

He had been master of the Bicester Beagles, and, like his brother, Horatio, had been decorated with the Military Cross for conspicuous service. During the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, the then Captain Fane, distinguished himself by completing a rear guard action from his gunning post and remaining on duty when his Major was wounded, despite him being slightly wounded himself. 37 out of the 40 men at his gunning post were either killed or wounded, one gun had been destroyed and another put out of action.

But the war wasn’t just focused on the Western Front. There were other theatres of war in Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Italy, not to mention the many actions taking place at sea.

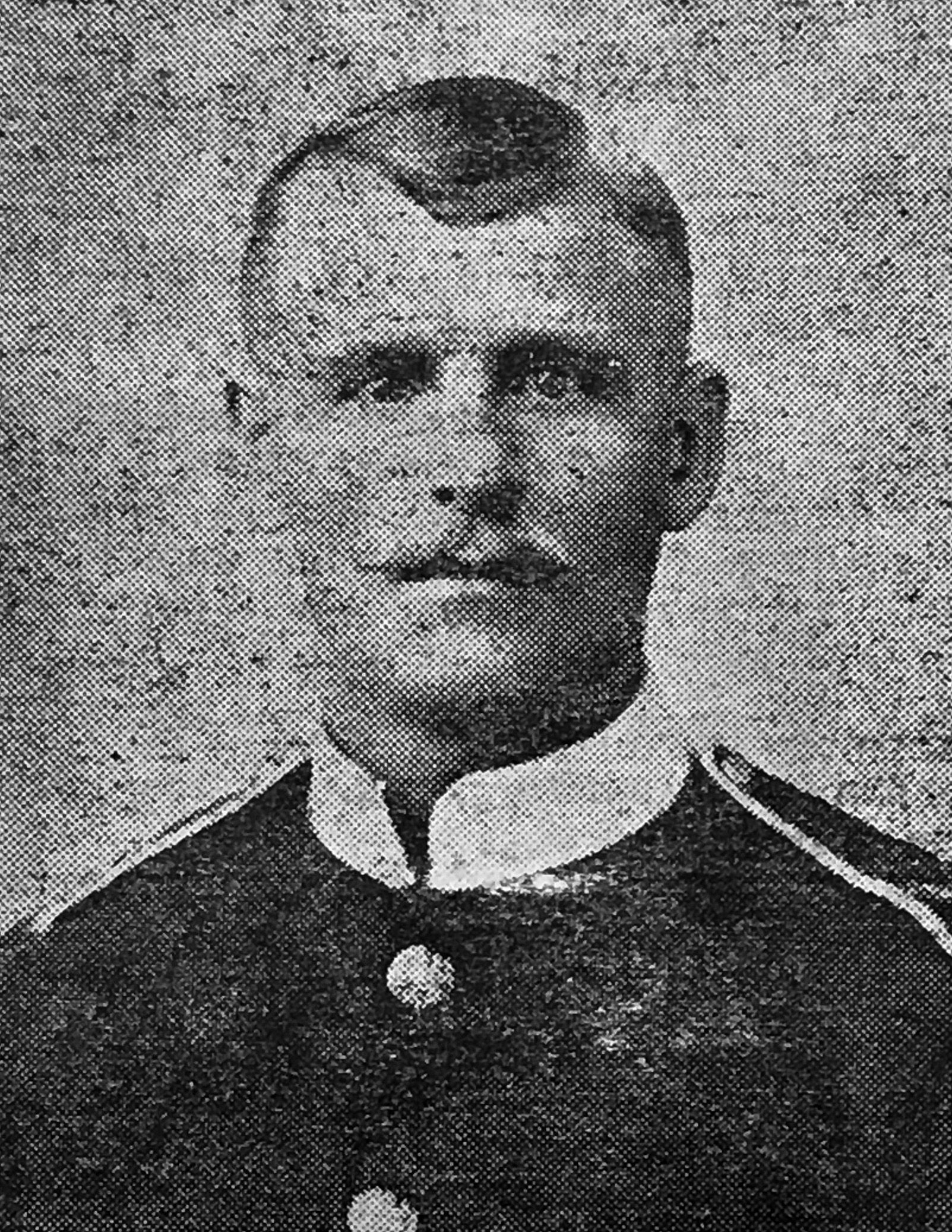

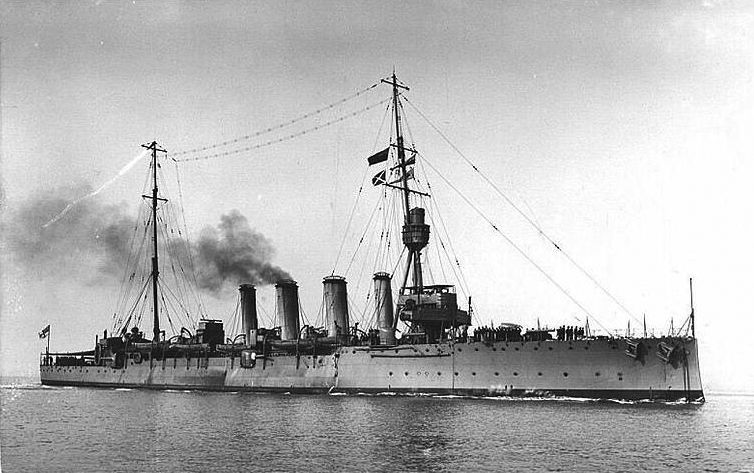

Engine Room Artificer Cyril George Pople Durrant, from Bicester, was serving aboard HMS Pathfinder when she was sunk by German submarine, U-21.

Cyril was the only son of Isaac George Pople Durrant and both of them were heavily involved with St Edburg’s Church for many years. The Reredos was erected in 1910, then later the figures within it were donated in memory of a number of people, including Cyril.

Cyril originally worked for the Steam Engineering Works at Cowley, and then took his engineering expertise all over the country before joining the Royal Navy and being appointed to the Pathfinder just before war broke out. He celebrated his 27th birthday aboard on 4th September 1914. Then on 5th September, just 5 weeks into the war, HMS Pathfinder was patrolling off St Abbs Head, on the south east coast of Scotland when, at 3:43pm, U-21 fired a single 20in torpedo from about 2,000 yards away. Lookouts on Pathfinder spotted the torpedo wake heading towards their starboard bow, and the officer of the watch attempted to take evasive action, but since the vessel was only traveling at five knots, any reaction was already too late.

The torpedo struck the ship beneath the bridge. The detonation set off cordite bags in the ship's forward magazine, which caused a second, more massive, explosion within the front section of the ship, essentially destroying everything forward of the bridge and front funnel. She instantly began sinking and within four minutes she was gone, dragging most of her crew down with her.

Fishing boats from a nearby port were the first on the scene and encountered a field of debris, fuel oil, clothing and body parts. Additionally, the British destroyers HMS Stag and HMS Express had spotted the smoke and headed in to help, only to find that the few survivors had already been rescued.

There were 268 personnel on board, plus two civilian canteen assistants. But there were just twenty survivors rescued from the water. Four of those survivors later died of their injuries.

Despite the events of that day having been easily visible from shore, the authorities attempted to cover up the fact that Pathfinder had been sunk by a torpedo, insisting instead that it had struck a mine. The true reason for this is unknown, but it was the first ever torpedo sinking of a ship and the Admiralty was probably trying to maintain the position that submarines — still a new and largely untested weapons platform — lacked the capacity to sink a surface warship with a torpedo. A local paper, The Scotsman, however, published an eye-witness account by one of the fishermen who had assisted in the rescue, that confirmed rumours that a submarine had been responsible. So admiralty intelligence later claimed that cruisers had cornered the U-boat and shelled it to oblivion. But still, the sinking of HMS Pathfinder by a submarine made both sides aware of the potential vulnerability of large ships to submarine attack.

Unfortunately that awareness didn’t come about in time to save another Bicester man, Able Seaman Thomas Hudson, who was serving aboard HMS Hogue, one of three obsolete Royal Navy cruisers of the 7th Cruiser Squadron, sometimes referred to as the "Live Bait Squadron", that was patrolling the North Sea, just off the Dutch coast, on 22nd September 1914.

A German U-boat, U-9, had been ordered to attack British transports at Ostend, but had been forced to dive and shelter from a storm earlier in the day. On surfacing, she spotted the three British ships, travelling at about 10 knots, and moved in to attack. At 6:20am, she fired a torpedo at the middle ship, HMS Aboukir, and struck her on her starboard side, flooding the engine room and causing the ship to stop immediately. No enemy vessels had been sighted, so the captain assumed that the ship had hit a mine and ordered the other two cruisers to close in and help.

U-9 then saw the other two British cruisers engaged in rescuing men from the sinking ship. Seising the opportunity, she fired two torpedoes at HMS Hogue, the closest of the two ships. As the torpedoes left the submarine, her bow rose up out of the water and she was spotted by Hogue, whose gunners opened fire before the submarine dived. The two torpedoes struck Hogue and within five minutes her crew were ordered to abandon ship. After ten minutes she capsized, before sinking at 7:15am. Watchmen on the third ship, HMS Cressy, had seen the submarine, opened fire, and even made a failed attempt to ram her. But they lost her when she dived and so turned to pick up survivors. At 7:20am, U-9 fired two torpedoes at Cressy. Both hit home and the ship quickly capsized, only to float upside down for about 30 minutes before she too sunk into the depths. Several Dutch ships began rescuing survivors about 30 minutes later.

The combined totals from all three ships were 837 men rescued, with 62 officers and 1,397 enlisted men lost. Of these, HMS Hogue lost a total of 48 men, including Able Seaman Thomas Hudson, of Field Street. He had served in the navy at the turn of the century, but had remained as a reservist after leaving the service. He worked for the Post Office in Bicester for about 8 years and when war broke out and he was immediately called up.

The disaster shook public confidence in the Royal Navy. Other cruisers were withdrawn from patrol duties and finally they started to take the submarine threat more seriously.

Meanwhile, Captain-Lieutenant Otto Weddigen and his crew on the U-9 returned home to a hero’s welcome. Weddigen was awarded the Iron Cross, 1st Class, and each of his crew received the Iron Cross, 2nd Class.

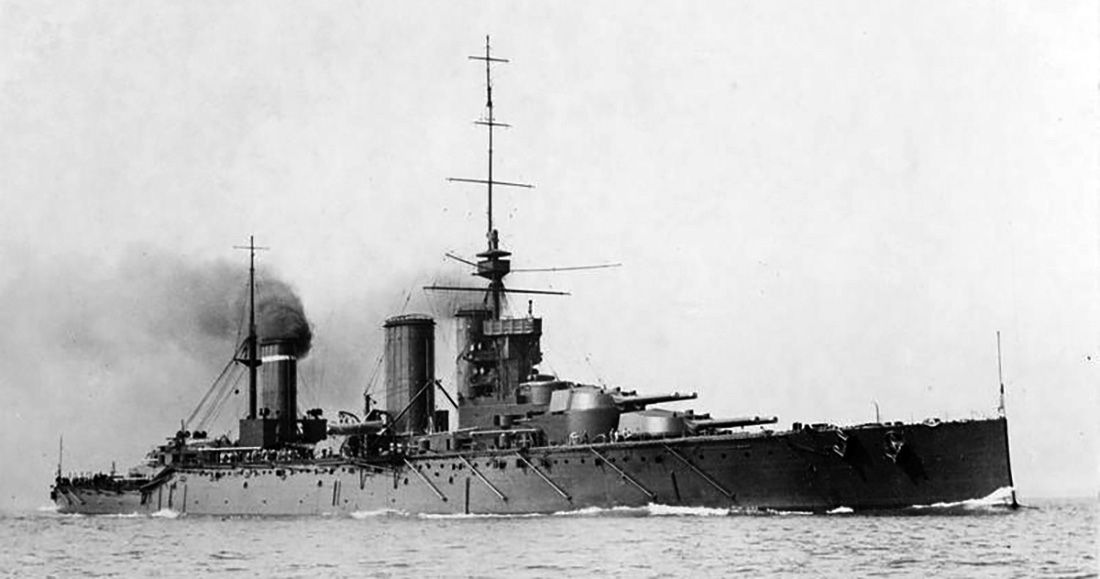

Luckily our naval inferiority didn’t last for long though. Seaman Thomas Jeacock, of Launton, serving on HMS Princess Royal in February 1915, wrote home to his family saying:

I suppose you have read of the action in the North Sea last Sunday, but I will give you an account of it.

We had reason to believe that another raid was intended on the coast, and early on Sunday morning we were steaming at a high-speed in search of the German ships. We were all ready and at our stations for action, when a number of battlecruisers and destroyers came up on the horizon. We immediately put on speed and steamed towards the enemy, who, on seeing us, made off at top speed. They were evidently not out to meet equals, but to bombard defenceless towns.

Our flagship, HMS Lion, opened fire, and soon we were giving it each other hot. We got several shots into them, and as each projectile weighs about 1200lbs, I think it tickled them up.

The Germans were now making off at top speed, firing as they went, but their shots were not on the map. The Lion was holed and left the line. Princess Royal, now being the first ship, led the Squadron. After we had made rings around them we engaged the Bleucher, who, seeing she could not escape, let fly with all her guns.

After a sharp action we could see that she was on fire, and one more “pill” from our 13.5s gave her the coup de grace. As she was settling in the water a huge airship hovered above, but it was “too fly” to get within range of our guns.

Eventually the Bleucher, which had been drifting around, capsized, and her boilers exploded, throwing up a high column of water into the air. Some of the German sailors were on the stern of the ship, and they jumped into the water as she dipped, being rescued by our destroyers.

We then went in chase of the other ships, which were burning fiercely, but we were in danger of mines and they escaped. I think they will take a very long time to repair.

Our squadron proceeded in the direction of England, after a fine action of three hours.

All the boys were very glad to get an opportunity of avenging the Scarborough business. If only their ships would give us a chance of a square fight, there would not be much left of them. Our ship escaped without a scratch.

I hope I have not seen the last of them, as I never enjoyed anything better than last Sunday forenoon.

Some naval encounters cost many lives but managed to stop short of losing the actual vessels involved. On 15th May 1917 HMS Dartmouth took part in the Battle of the Otranto Straits after a force of three Austro-Hungarian cruisers carried out an attack on the Otranto Barrage (an Allied naval blockade of "drifters" across the Adriatic Sea, between Brindisi in Italy and Corfu).

The attack started at about 4:20am, when fourteen of the lightly armed drifters were sunk and four more damaged. The Dartmouth left Brindisi at 5:36am in company with two Italian destroyers, they were joined in the pursuit of the Austro-Hungarian cruisers by an Italian scout ship and the British cruiser HMS Bristol.

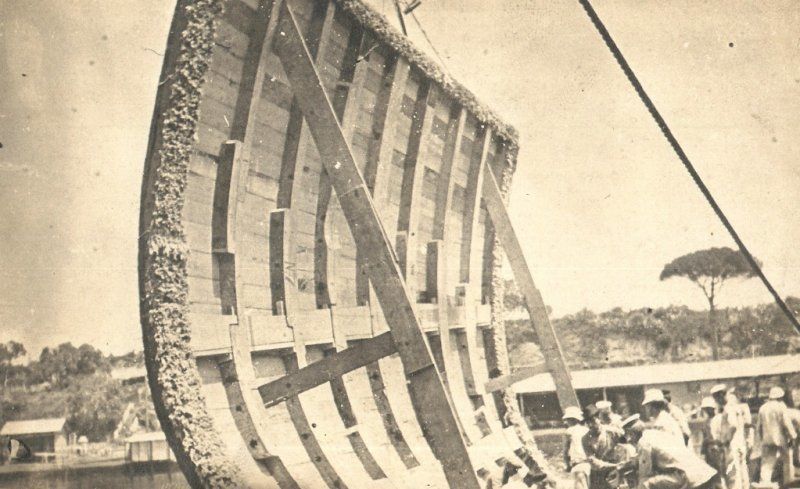

Dartmouth was hit several times by shellfire from the cruisers and had to heave to. Returning to port alone, she was then hit by a torpedo from the German submarine UC-25 and began sinking. The order to abandon ship was given, but a small team volunteered to remain on board and keep her afloat while she was towed to port.

They threw a canvas over the side to slow the water up and got the pumps running. They even shored up the hole with broken up furniture, mattresses and anything else they could find to stop the worst of the water coming in.

After limping back into Brindisi, the Italians sent down divers who made a "mould" of the hull shape and then they built a wooden coffer dam, which they used to patch the hole. Dartmouth then sailed all the way back to Portsmouth at a nerve-rackingly slow 15 knots, with the coffer dam in place. She was then dry docked and repaired, and went on to survive the war, eventually being sold for scrap in December 1930.

Unfortunately, not all of her crew were so lucky. The torpedo explosion killed eight of the crew onboard, including one Commander Robert Fane, the fifth son of Captain Henry and Mrs Blanche Fane, who were living in Bicester House at the time.

Born in 1882, he chose the Navy as his profession from a very young age. As a boy he was taught by a naval tutor in Greenwich and was first appointed to the battleship “Victorious” as a cadet. He sailed aboard her to China, returning on board the “Revenge”. He then joined the “Vernon”, on which ship he studied a course on electricity.

He later went to sea again, this time on the “Bellerophon”, by which time he had received promotion, and upon leaving her he again returned to the “Vernon”, now in the capacity of an instructor.

When war broke out he was appointed to a responsible post on the Forth defences, and then in 1915 he was appointed to the “Dartmouth” as Commander, where he served until his death.

A grave in Brindisi contains the remains of the five crew who were found, but also commemorates the other three whose bodies were never recovered.

Whilst all that was going on at sea, the Allied forces decided that it would be a good idea to invade the Ottoman Empire and seize control of their capital city, Constantinople, now known as Istanbul. This would give them a clear supply route to Russia from the Mediterranean.

The invasion, overseen by First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, became known as the Gallipoli Campaign, and ultimately proved to be a costly failure.

Of all the various parts of the world where Allied forces were deployed during the First World War, Gallipoli was remembered by its veterans as one of the worst places to serve and it was the scene of some of the fiercest fighting of the war. After failed naval attacks on the Ottoman coastal fortifications in February 1915, Allied troops landed on the Gallipoli peninsula in early April. They then spent months on the small peninsula of land without getting much further.

The peninsula was unsuitable for the lengthy campaign that took place there. The terrain was inhospitable, characterised by rocky ground with little vegetation and hilly land with steep ravines. After the initial assaults in April 1915, the Allied invasion lost its momentum in the face of strong Turkish resistance. Complex trench systems developed as the situation descended into an uneasy siege-like state. In some places, the Turkish and Allied lines were just a few dozen metres apart.

Ultimately, the military aims of the campaign in Turkey were not achieved and it was eventually called to a halt. The final Allied troops were evacuated in January 1916, but by then there had been many casualties, not only from the fighting, but also from the extremely unsanitary conditions. Of the estimated 213,000 British casualties, 145,000 were from illness. Surviving combatants also recalled the terrible problems with intense heat, swarms of flies, body lice, severe lack of water and insufficient supplies.

It was here that Private Charles Coles died following an engagement on 6th August 1915. He was 19 years old and well known in Bicester. The son of George and Amy Coles of Tinker’s Lane. He worked in Tubbs Bank until his enlistment on 9th March 1915 and had also been quite involved with the Church Lads’ Brigade.

He originally joined the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, but later transferred to the Worcestershire Regiment. After his initial training he was sent out to Gallipoli, arriving in early July. Almost immediately he wrote home about his first experiences of fighting the Turks, only to be reported missing just a few days later.

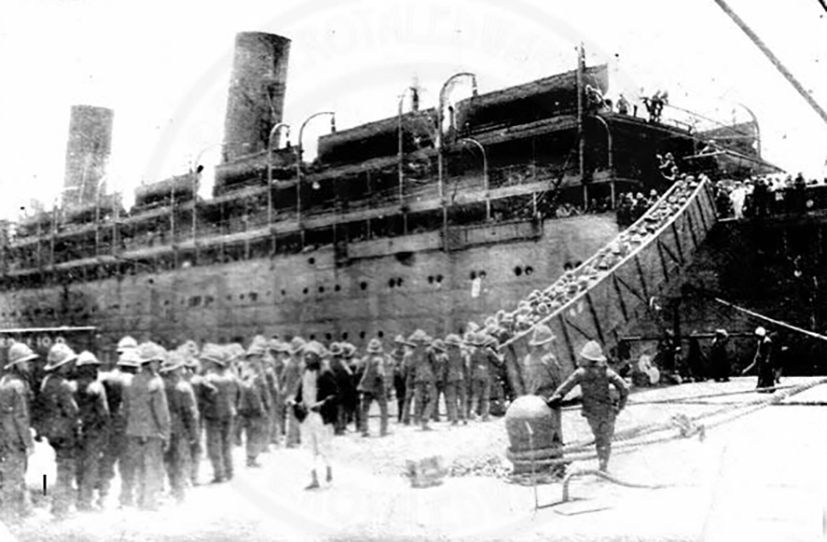

Private Coles may have only been on the peninsula for a short time when he died, but at least he actually made it there. Unlike Lance-Corporal William Alldridge, a native of Bicester, who sailed all the way there, only to be killed on 13th August 1915 when his transport ship, the Royal Edward, was torpedoed by a German Submarine, the U-14, and became the first troopship to be sunk in the First World War, just a few miles from the Gallipoli peninsula.

Troops had boarded HMT Royal Edward at Avonmouth on 28th July 1915 to sail to Gallipoli. She was carrying 220 crew, 31 officers and 1,335 men. Before reaching her destination the ship docked at Alexandria on 11th August to exchange supplies and allow the men to stretch their legs on a route march through the city.

The following day, with the men back in their now familiar routine, the ship made her way through the French patrolled waters towards the Gallipoli Peninsula. Suddenly, from out of nowhere, a torpedo struck her port side, just behind the engine-room. There was a terrific explosion, the ship shuddered from bow to stern and began to sink. None of the men were wearing their lifebelts, so their first thought was to get them – but this meant going below to their bunks where the lifebelts were stowed.

Hundreds of men already below, desperate to reach the decks and the lifeboats, met on the companion ways with hundreds of men trying to go below. Some were crushed or beaten aside in the panic. The lights went out. Those who reached their bunks were trapped by the speed of the rising water and tried in vain to escape through the too small portholes. Others were simply overwhelmed by the rushing in of the sea.

Within three minutes the aft deck was submerged and the bow was raising high into the air, and in just six minutes she slid beneath the waves, still with the majority of soldiers below deck.

Her wireless operators were able to get off an SOS before they lost power, and the Hospital Ship Soudan quickly arrived on the scene to rescue survivors. The final death toll varies from source to source, but it is widely accepted that ultimately 935 men died as a result of the sinking.

We don't know exactly what happened to Lance-Corporal Alldridge, but on 10th September 1915 the Bicester Herald printed the following report:

At the time of the sinking of the “Royal Edward” on the 15th of last month it was conjectured that a Bicester soldier in the person of Lance-Corporal W.J. Alldridge was on board. Monday’s list of casualties in connection with the loss of the transport confirmed this supposition, much to the regret of all who knew this keen soldier, who enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps nearly twelve months ago.

The deceased was the second son of the late Mr and Mrs W. Alldridge, of Bicester, and was 26 years old. At one time he was employed as an assistant at the Bicester branch of the International Stores, and afterwards worked his way up to the post of manager at Chelmsford. He was a “non-com” in the local detachment of the Church Lads Brigade, and when a boy was a member of the Bicester Church Choir.

It is a matter of considerable disappointment that he met his death before having had an opportunity of taking part in any of the actual fighting.

Meanwhile, things were starting to heat up in Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq. The Ottoman Empire had conquered the region in the early 16th century, but never gained complete control. Regional pockets of Ottoman control through local proxy rulers maintained the Ottomans' reach.

By 1914 the Anglo-Persian Oil Company had obtained exclusive rights to petroleum deposits throughout the Persian Empire, including areas controlled by the Ottomans. And just before the war, the British government had contracted with the company for oil for the navy.

Shortly after the European war started, the British sent a military force to protect Abadan, the site of one of the world's earliest oil refineries. British operational planning included landing troops in the Shatt-al-Arab. The reinforced 6th Division of the British Indian Army was assigned the task.

In November 1914 the British offensive began and by the end of the month the British Indian Army had occupied Basra, allowing them to protect the oilfields they needed.

Things then simmered away for some time until, after defeating a large Ottoman offensive in April 1915, the War Office started to take interest and ordered the army to advance towards Kut-al-Amara, or even Baghdad if possible. They captured the city of Nasiriyah in July 1915, and with it the Ottoman's largest supply depot in the region.

In late September 1915, amidst the recent defeat of Serbia and entry of Bulgaria into the war, and concerns about German attempts to incite jihad in Persia and Afghanistan, the Foreign Secretary encouraged the further 100-mile push to Baghdad. The army thought this logistically unwise, but Kitchener advised that Baghdad be seized for the sake of prestige, then abandoned.

So the British pushed on and took Kut-al-Amara. But on the 7th December, the Ottoman siege of Kut began, and lasted until the British forces in the city surrendered on 29th April 1916, all 13,164 of them becoming prisoners of the Ottomans.

Whether he was one of the men under siege, or one of the ones trying to rescue the besieged city, we don't know. But Second-Lieutenant Alfred Holloway Truman, of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, was killed in action at Kut on 6th April 1916. On 14th April the Bicester Advertiser wrote:

He was the eldest son of Mr and Mrs Alfred Truman, of “Littlebury”, Bicester, and was nineteen years of age.

He was educated at Oxford High School and passed the Senior Local Examination in 1914 and Responsions in March 1915, when he entered St John’s College, Oxford. On 4th May 1915 he was gazetted a 2nd Lieutenant of the 3rd Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, and was confirmed in the rank on 20th December 1915.

All who knew him will regret the end of a very promising career. Lieut Truman displayed much activity as an athlete, and was a well-known member of the Bicester Cricket Club.

The British refused to let the defeat at Kut stand. Further attempts to advance in Mesopotamia were ordered by the War Office, so the British forces regrouped, reorganised and retrained, determined to succeed this time. It took them 11 months, but on 11th March 1917 they entered Baghdad and were greeted as liberators.

Unfortunately, one local man never saw the victory of the British that he had been working towards. Corporal Frank Powell, of the Welsh Regiment, died in the Amara Isolation Hospital in Basra, on 3rd July 1916, after suffering from a severe attack of colitis. He was 22 years old.

It was reported in the Bicester Advertiser that he was attached to the Indian Expeditionary Force, and after serving unscathed through the whole of the Gallipoli campaign (being one of only nine surviving members of his company), he had taken part in the attempted relief of Kut-el-Amara.

In a letter received by his mother at the beginning of July, but dated two months previously, he said he was then quite well, and added:

I don’t know what they are going to do with us, but it is about time they sent us home. We have done our share, and I suppose the people are making a row in England about us being out here so long.

I wish this place was not so hot; it is 110 degrees in the shade, and worse than India. You will see an account of our fighting in the paper; they call us a fine name – The Iron Division – and it is about right after the way in which we have stuck it.

Then writing on 24th May he said:

I am glad to tell you that I am alright at present. We are getting some terrible weather out here; you would never believe it could be so hot. I suppose you have heard about the advance we have just made, and how they call us the Iron Division, and our men must be made of iron to stand this weather for twelve months. I do not think this will last much longer, as we have now joined hands with the Russians, and they have got the Turks nearly beat.

The Allied struggle against the Ottoman Empire also included battlefronts in Egypt. Fighting in Egypt and Palestine had begun in February 1915 with Turkish forces attempting to breach British defences on the strategically vital Suez Canal. Seizing it would cut British communications with East Africa, India and Asia, and prevent British Empire troops from reaching the Mediterranean and Europe. But the British had expected the offensive and were well prepared, having fortified the length of the canal. The fighting lasted two days with the Turks losing over 2,000 men, while British losses were minimal.

Throughout the rest of 1915 and 1916, the British were content to just guard the Suez Canal and their territory in Egypt. But defeat at Gallipoli dashed any hope of a quick victory over the Ottoman Empire. Defending the canal from possible Turkish attack also required manpower the Army could not sustain, especially with the ever-growing demand for troops on the Western Front. So, in 1917, it was decided to push the Turks out of the Sinai peninsula.

This began as a test of endurance and military engineering in the harsh terrain of the Sinai desert, but evolved into a fast-moving mobile campaign through Palestine and Syria, which ultimately resulted in a decisive Allied victory and the eventual fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Quite a few men from the local area served in the Egypt Campaign, and three of them lost their lives there including Private Samuel Pitts, a native of Bicester, who was serving with the Royal Army Medical Corps when he was killed on 30th October 1917.

Private Aubrey Herring, the youngest son of Thomas Herring, a grocer in Sheep Street, died from wounds on the 11th November 1917 in a hospital in El Arish. His elder brother, Thomas, was serving nearby at the time, but we don't know if he was able to visit Aubrey before he died.

The third was Second Lieutenant John Woodall, from Islip, who died on 8th November 1917. He first joined the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry in August 1915 and then transferred to the Machine Gun Corps in January 1916, serving in France, where he was awarded the Military Cross for rushing a machine gun up to the crater of a newly exploded mine and holding off the enemy for 40 minutes whilst his colleagues withdrew. He was severely wounded in the incident, but after recovering he returned to service and proceeded to Egypt in June 1917, where he served until his death.

Before the war, Italy was part of the Triple Alliance, together with Austria-Hungary and Germany. But Italy did not declare war in August 1914, arguing that the Alliance was defensive in nature and therefore Austria-Hungary's aggression did not obligate Italy to take part.

This gave the Allied nations a chance to muscle in. Allied diplomats secretly courted Italy during the first few months of the war, attempting to get them to come over to our side. It was finally engineered by the Treaty of London on the 26th April 1915, in which Italy renounced her obligations to the Triple Alliance. Then, on 23rd May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary.

The Italian Front, or Alpine Front, formed along the border between the two countries. Italy had hoped to gain their territorial objectives with a surprise offensive, but the front soon bogged down into trench warfare, similar to the Western Front in France, but at high altitudes and with very, very, cold winters.

The two countries continued to fight it out between themselves until October 1917, when, after an Italian offensive almost destroyed the Austrian army on the front line, German troops were brought in to assist their Austrian allies. They brought with them new tactics and gas weapons and drove the Italians back about 12 miles to the Tagliamento River.

Then, in November 1917, British and French troops were brought in to bolster the front line on the Italian side. They also brought with them new strategies and much needed resources, and helped to even-up the two opposing sides again.

One of the British troops brought in to fight on the Italian Front was Sergeant John Grimsley, serving with the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. His parents, living in King's End, received a letter from one of his comrades at the end of June 1918 telling them that he had been killed in action on the 15th of that month.

The letter stated:

The enemy had made a big push and had succeeded in breaking through. A counter attack was launched, and it was during this that Sergeant Grimsley met his death. At that time the English were fighting against odds of four or five to one. The unfortunate soldier met his death almost instantaneously, having a machine gun bullet through his side, one through his leg, and another through his head. He was buried in a British cemetery two days later.

Another letter, this time from one of his officers, said:

As I have been his platoon officer for the last ten months I knew him very well, and I have never met a more honest, brave and staunch supporter.

The Austrians attacked our positions at dawn, and your son was in the thick of it, and fought to the last against greatly superior numbers. He was killed instantaneously by a machine gun bullet, and his death is a great loss to me and to the platoon.

Sergeant Grimsley was in the Oxfordshire Yeomanry when the war broke out. Previous to that he had served in the Church Lads’ Brigade, in which corps he was a sergeant and bugler.

He took a great interest in the YMCA and, besides being a member of their band since its formation, did much good work for that institution. He was a staunch supporter of the Primrose League, a member of the Bicester Rifle Club and the Bicester Football Club.

He joined the Territorials in 1913, was mobilised on the 5th August 1914, went to France in March 1915, and from there to Italy, where he remained until his death. He went out as a private, but gained quick promotion having been a sergeant for over two years prior to meeting his death. He was 23 years old.

Back at home in Britain many men were dying in hospitals all over the country from wounds they had received on active service abroad. But illness was also a fairly common cause of death during the war, and some men, like Private Ernest Pitts, of Bardwell Terrace, never even made it abroad.

Ernest died on 2nd January 1918 at Connaught Hospital, Aldershot, after a lengthy suffering with bronchitis. He was working as a shoeing smith for the Royal Engineers, preparing the horses for their vital work abroad.

He had been afflicted with Asthma since he was 14. But four months after joining up he was admitted to the hospital in April 1917 when he started coughing up large quantities of puss. This continued off and on until mid-November, when his condition rapidly worsened. His temperature dropped to below normal and his abdomen began to swell with fluid, which required frequent tapping and draining. After a month of this his body finally gave up the fight.

He is officially recorded as having "died of heart failure following severe bronchitis, aggravated by military service". Over his one year in the army, he had spent a total of 61 days in hospital.

Richard Woodhouse died in Oxford, on 2nd September 1917, from tuberculosis. He had enlisted in the Army Veterinarian Corps on 14th June 1916, but was discharged and awarded a Silver War Badge four months later on 16th October.

We don't know for certain that TB was the reason for his discharge, but the Silver War Badge showed he was unable to serve because of poor health. The badge was issued in the United Kingdom and throughout the British Empire to service personnel who had been honourably discharged from military service due to wounds or sickness. It was introduced as an award of "King's silver" for having received injury during loyal war service to the Crown's authority.

A secondary cause for its introduction was that a practice had developed in the early years of the war where some women took it upon themselves to confront and publicly embarrass men of fighting age that they saw in public places who were not in military uniform, presenting them with the dreaded white feathers as a suggestion of cowardice. So, as the war developed, substantial numbers of servicemen who had been discharged with wounds that rendered them unfit for war service, but which were not obvious from their outward appearance, found themselves being harassed and humiliated without cause, and the badge was a means of discouraging such incidents being directed at ex-forces' personnel.

There were also people who served abroad, and then had time to come home before their illness caught up with them. Like Mary Hombersley, of Islip, the only female recorded on any war memorial in the area.

She had been working as a nurse in Serbia where she is believed to have developed the malignant bowel cancer that ultimately led to her death. She suffered with it for two years before having it operated on at a military hospital in Reading. The surgery itself was a success, but she suffered complications during her recovery and died there on 27th November 1917. She was 55 years old.

Even civilians in Britain weren’t safe during the war, the Bicester Advertiser in February 1915 reported that:

Miss Lawrence, former housekeeper for Mr H.C. Jagger, at Bicester, had an unpleasant experience during the recent air raid at King’s Lynn.

It appears that a Zeppelin hovered over the house in which she was living and dropped two bombs. One falling in the garden at the rear of the house, unexploded, whilst the other went straight through the house and penetrated the ground to a distance of about 6 feet, doing considerable damage.

Miss Lawrence, although being much shaken, was fortunately not injured, and the rest of the house’s occupants were away at the time.

Miss Lawrence is sure to be congratulated by her many Bicester friends on her fortunate escape.

The fighting officially ended when the Armistice with Germany was signed on 11th November 1918.

Private Herbert Wise, a native of Charlton-on-Otmoor, died on 6th November 1918 in Bulgaria, making him the last local man to die before the Armistice was signed. He had been held as a prisoner of war until the Armistice with Bulgaria was signed on 29th September, but was sadly too ill to leave straight away after being released and died before he ever made it home.

These days we consider the Armistice on the 11th November to have been the end of the war. It certainly was an end to the fighting, but the Armistice was prolonged numerous times before peace was finally ratified at 4:15pm on 10th January 1920.

The Armistice may have been an end to the fighting, but unfortunately it wasn't an end to the deaths. Another 7 local men had died from their wounds by the end of 1918, and 4 more died the following year. Merton and Bicester's war memorials both record men who died in 1920. Whilst Weston-on-the-Green's records one man who died in 1921 and Islip's records a man who died in December 1922. Petty Officer William Sherrell, who is the last recorded local man to die as a result of the Great War.

After the Armistice, and once the celebrations had ended, people began to look back on what and who they had lost and wanted to memorialise it all in some way. On 6th December 1918 the Bicester Advertiser reported on a recent Urban District Council meeting where Councillor Malins had said:

The time has come to prepare for some permanent memorial to remind us, and those who come after us, of the supreme sacrifice in the Great War.

It had been nobly said, that those who had made the supreme sacrifice, in vindication of all that was good and for the advancement of humanity, were the heroes of God, as those who had been permitted to survive the awful carnage, were the heroes of man.

Every town and village will do something to remember those who have gone to an early grave, and I think it is time some memorial is thought about here."

And so a committee was set-up to deal with it. But, in typical committee fashion, they umm’d, and ahhh’d, and made very little progress for a few months, until it was decided that they would put the few options they had come up with to a public referendum. These options included buying Bicester Hall (now Hometree House) to use as a new Town Hall, which was, coincidentally, the option that the councillors all seem to have been mostly in favour of.

However, the public vote came back with a majority in favour of them providing a recreation ground for the town. By now it was September 1919, and, not happy with the result of the vote, they reluctantly set up a new sub-committee to carry out the will of the people. But, at the first meeting of the sub-committee, only eight of the twenty councillors involved actually bothered to turn up. For those that did persist with it, almost immediately the issue of funds came up, and it eventually just seems to have gone quiet.

However, in the mean time, another committee, this one of parishioners and the vicar at St Edburg's, were making progress with their own memorial idea.

Only a week after the council's failed first sub-committee meeting, Rev. Walter O’Reilly announced that they were going to erect a churchyard cross in the fashion of the old Oxfordshire crosses, made from Portland and Ancaster stone, on the small triangle of grass between the porch of the church and the vicarage.

They planned to have the names of the fallen carved on the steps of the memorial, and have another memorial inside the church bearing the same names. The cost was estimated at £350, all to be covered by public subscriptions.

The fund-raising seems to have been successful, as the memorial was unveiled by Captain Fane at a dedication ceremony on Thursday 10th February 1921, and it still stands today. They never managed to get the names carved into the base, opting instead for just having them on a tablet inside the church porch.

There do seem to be some glaring omissions in the list of names though, mostly for no clear reason. The most unusual being Private Charles Coles, who died in Gallipoli. His name being missing from the stone is odd, because two of his brothers are listed and he was included on the list of names published in the order of service for the memorial's dedication ceremony.

At the dedication ceremony the Lord Bishop of Oxford said:

It is good that in every parish throughout the country there will be a memorial – a tribute of loving, grateful memory to the sacrifice of loyalty of their brothers, because to people of a hundred years hence, it shall come home to them, they will see there was no parish and scarcely a home that was not touched. They will pause and they will think of the sorrow, and bereavement, and anguish of the cutting off of those to whom England was looking to carry on her great traditions.

Well, we are the "people of a hundred years hence" and I'd say that the impact of the sacrifices that those I’ve talked about here and the countless others made are just as keenly felt today as they were back then, and I’m sure that they will be for many years to come.