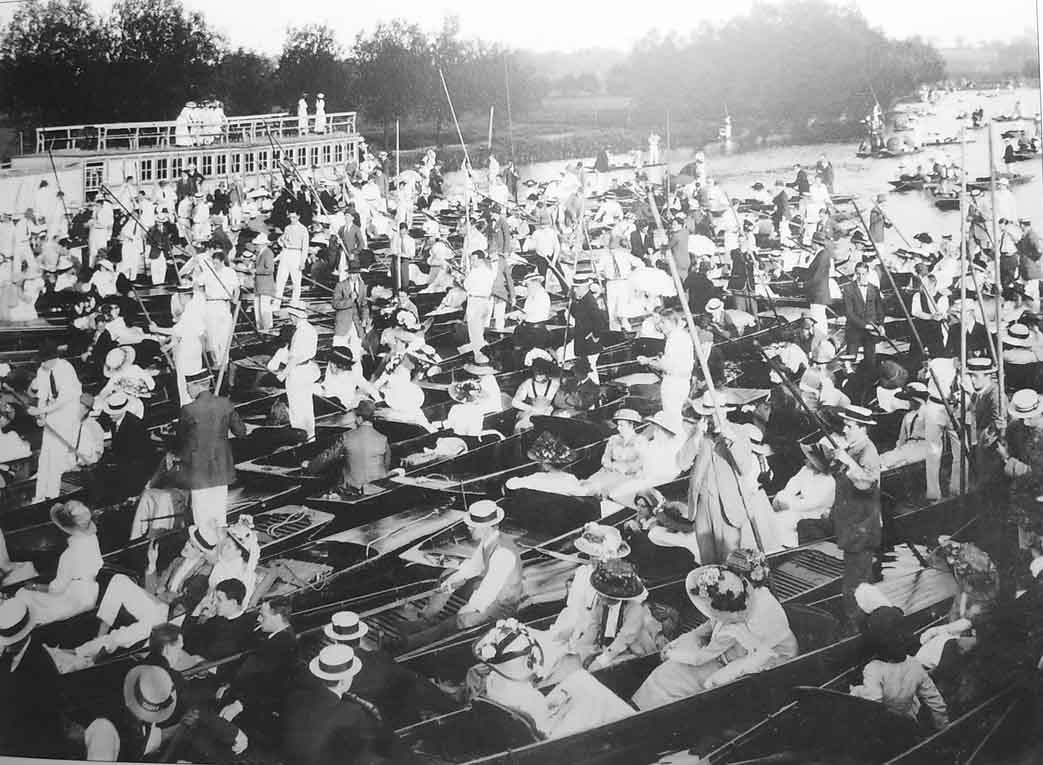

Eights Week at Oxford

One of the previous incumbents of St Edburg’s Church, Reverend Charles Cowland-Cooper (who was vicar in Bicester from 1942 until 1953), originally studied theology at Keble College, Oxford. Whilst at Keble his spare time seems to have been mostly devoted to punting and tennis, but he still found time to write to his old boarding school, Abbotsholme School in Staffordshire, and contribute regular articles for their school magazine.

In a piece written in 1905 he talks about the events of Eights Week in Oxford as follows:

To an old 'Varsity man the term “Eights Week" instantly conjures up a sparkling picture of days of perfect holiday and of that loyal devotion to worldly pleasure which youthful undergraduate minds are so capable of attaining.

But there are those to whom such a term is altogether meaningless, and who have never participated in one continuous revel of seven days' picnics, punts, and pretty cousins; and we feel it is our duty to enlighten them, offering some meagre interpretation, that they may realise we can boast not only of intellectual pinnacles, but of giving a magnificent exhibition to the world of how a young man ought to play. Now it generally takes a 'Varsity man some one or two years' experience before he can really sift an eights-week programme, and learn to pick out the most succulent plums; and it was a great delight to me this last summer, when I had an Old Abbotsholmian stopping with me, to perceive with what instant and masterly skill he descried between good and evil. I think it is no mean compliment to Abbotsholme that, so far from being at all out of his element in these purely local festivities, he flung himself into the vortex of enjoyment with a zest and heartiness that would have done credit to an epicure of many years’ standing. Blessed with perfect weather, we were out of doors practically all day long, and as the we included a fond parent and two girl cousins, not forgetting numerous Japanese umbrellas and an enormous hamper, we formed quite a nice and compact little punt full of rippling gaiety and innocence.

On most days our programme was the same. A breakfast party for eight in one’s rooms generally opened the morning’s proceedings, and as there was always a good deal more talking than eating, it was always about 10:30 before we made a move to pipes and easy-chairs; this was regularly followed by a discussion as to whether it would be more profitable to wander into College Gardens and Dining Halls, or to embark on our favoured craft and seek the shade of inviting willows and the accompaniment of “pipes and cousins”; this knotty point once settled, the morning passed rapidly away.

At about three o'clock – unless we had taken lunch on the river with us – we joined a scrambling, pushing crowd at Parson’s Pleasure, where fifty people tried to get into their punts at the same time, and where consequently nobody could do anything. Once, however, comfortably stowed on board, we slowly dropped down stream in a long line of punts and canoes, each bearing its precious burden towards the same goal – a position to watch the racing of the College crews.

I wonder how many Abbotsholmians have punted. Let the rest lose no time, but try it at once! My Old Abbotsholmian visitor proved himself an adept at the art. He lost his pole, he described tortuous circles and semi-circles, he constantly stopped other punts, and at all times displayed a generous liberality in the matter of pouring water on trousers and frocks; in this performance at any rate he stood without the least shadow of a doubt second to none.

Between the heats of the racing, one partook of a picnic tea either on board or on a shady bank, and finally tore back home to change for the theatre or a dance.

This is a very weak account of a typical day, but one must remember that it is the many accompanying incidents rather than the main features that are mainly responsible for the pleasing impression.

I remember one afternoon, whilst we were quietly enjoying tea under a shady tree, we suddenly spied another famous Old Abbotsholmian feverishly oscillating an enormous punt to and fro in the vain hope that among three thousand people he would discover a party of five - four of whom he had never seen before – whom he had quite missed through going to the wrong landing stage; it was a most heartrending spectacle. He had spent hours on completing a faultless toilet, and we were grieved that we could offer no enlightenment.

Last eights week saw four Old Abbotsholmians enjoying its full bounties, and I think we proved worthy of the old place in doing ourselves thoroughly well, and getting out of our time every possible particle of fun and enjoyment. Can we not reasonably trace back causation, and say that there is surely no school in England that gives a boy a better preparation for Oxford than Abbotsholme? For Oxford’s influence does not lie in her examinations or her degrees, but rather in affording a unique chance for the development of personal judgement and discrimination – for choosing between what is useful and worth pursuing, and what is useless and to be thrown aside.

It would be difficult to find more favourable circumstances for this important step in the strengthening of one's character, coming as it does at one of the most critical moments in life; where else will one hob-nob with every conceivable type of character, or have offered so large a variety of pursuits and past times? And if one compares his previous training at Abbotsholme, and the lines upon which it was based, with the almost entire lack of real development of character shown in the products of other public schools, he sees immediately the reason why there is no boy who is more fully equipped or prepared, or more likely to embrace all the good that the place has to offer, than is the Abbotsholme boy when he becomes an Oxford man.

- C.P. Cooper